Practical Approach to Evaluating Requests to Test New Antimicrobials

8/15/2019

Written By: Catherine A. Hogan, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

Many new antimicrobials have recently come to market to address the rising threat of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria. Clinical and public health laboratories are critical participants in the management of patients with MDR infections and must develop a plan for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of these new agents, either in-house or at a reference laboratory.

Herein, we present an example of a practical approach to this challenge. Let’s consider how a laboratory might respond to the scenario of receiving the following request from the institutional antimicrobial stewardship team:

“Can the laboratory start testing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) for ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA; AVYCAZ®) susceptibility?”

1. Consider the clinical need

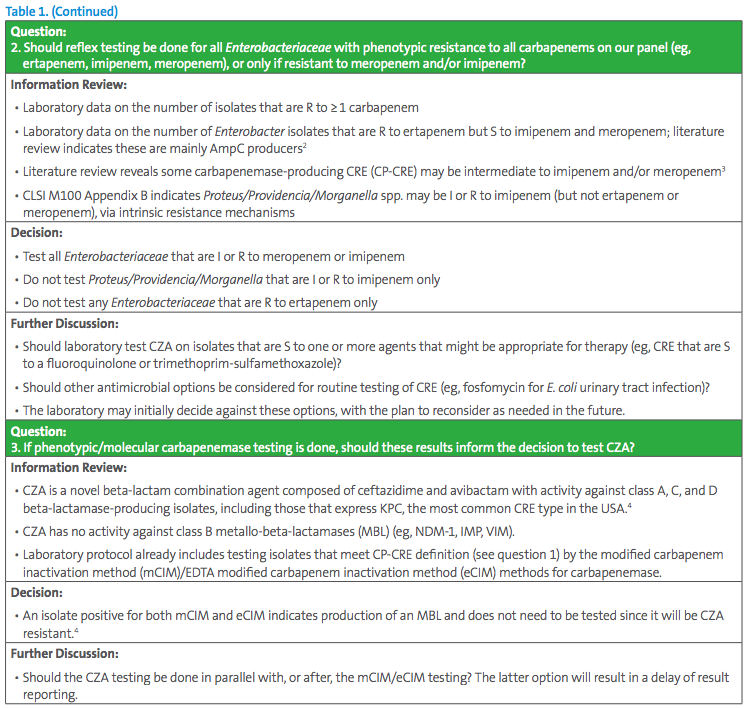

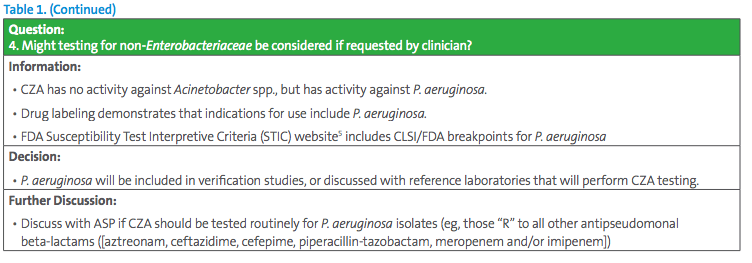

The Antimicrobial Stewardship Program (ASP) chair has requested all CRE be tested for CZA susceptibility. This request seems simple, but careful consideration should be given to different testing approaches. Some key questions for the laboratory to consider are listed in Table 1.

2. Testing in-house or send out?

This question requires consideration of:

• Expected volume of testing, based on the number of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae from last year’s antibiogram

• Availability of testing options and materials

• Capacity to perform testing in-house

• Staffing capacity to perform verification studies, write standard operating procedures (SOPs), etc.

• Impact of testing option(s) on turnaround time to results

A basic cost-analysis of in-house vs send-out testing should be performed, keeping in mind that the results of testing CZA are often critical to patient care. Close collaboration with infectious diseases, critical care physicians, laboratory medicine, and administrative colleagues is essential to ensure an optimal workflow. For the purpose of this exercise, let’s assume the laboratory encounters ~100 isolates per year that meet the testing criteria defined in Table 1, and determines testing should be done in-house.

3. How to perform the verification studies?

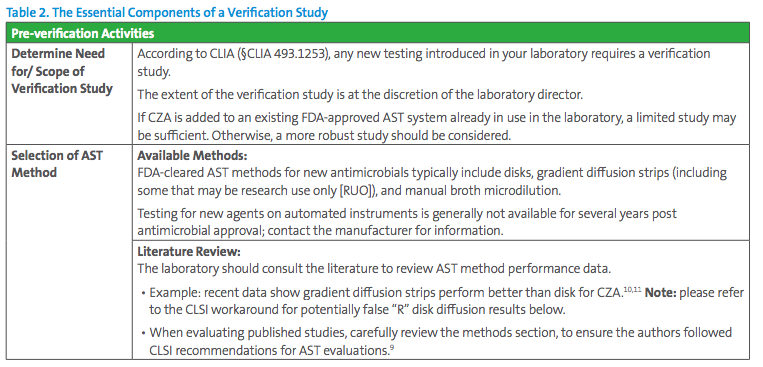

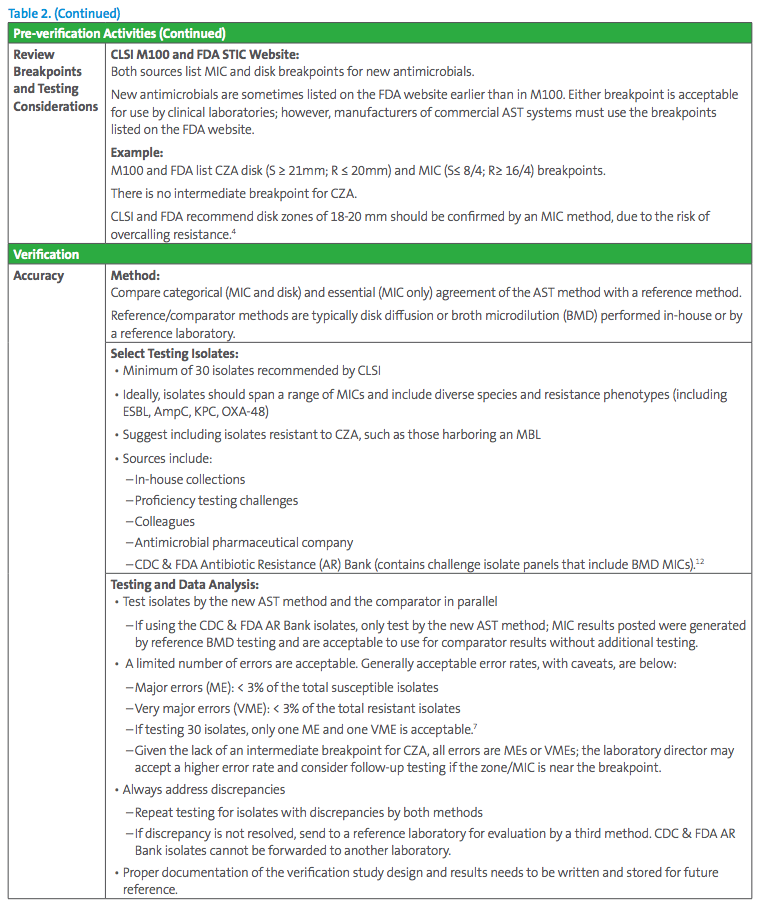

The essentials of a verification study are presented in Table 2; further guidance is found in references.6-9

4. How to perform QC? Should we consider an IQCP?

CLIA requires the laboratory either performs AST QC daily or develops an Individualized Quality Control Plan (IQCP).4 In many laboratories, CRE are relatively uncommon and CZA will be tested infrequently (ie, less than once a week). As such, the laboratory may choose to not perform an IQCP, but to do QC each time a patient isolate is tested.

5. What results should I expect? (ie, how often are carbapenem-resistant isolates R to CZA?)

In vitro susceptibility rates of Enterobacteriaceae to CZA are very high, with > 99.5% susceptibility overall, and > 97% among class A and D carbapenemase-producing isolates.13,14 In contrast, as highlighted previously, little to no activity is expected against MBLproducing Enterobacteriaceae. If the laboratory encounters a high rate of resistance, this should be investigated to ensure it is not due to technical error. In summary, broad-spectrum agents such as ceftazidime-avibactam have strongly enhanced the therapeutic arsenal against MDR gram-negative organisms, an important cause of morbidity and mortality in patients in hospitals and long-term care facility settings. Implementing testing and completing a verification study for a new antimicrobial agent such as CZA carry additional workload which may seem daunting to the laboratory. However, accurate and timely microbiological testing is instrumental in identifying effective therapies that may significantly impact patient outcomes and enable effective resource allocation.

References

1 US Food and Drug Administration. Access data. 2018; https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/206494s004lbl.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2019.

2 Yang FC, Yan JJ, Hung KH, Wu JJ. Characterization of ertapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae in a Taiwanese university hospital. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(2):223-226.

3 Karlowsky JA, Lob SH, Kazmierczak KM, et al. In vitro activity of imipenem against carbapenemase-positive Enterobacteriaceae isolates collected by the SMART global surveillance program from 2008 to 2014. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(6):1638-1649.

4 CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 29th ed. CLSI Supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2019.

5 US Food and Drug Administration. Antibacterial Susceptibility Test Interpretive Criteria. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/ucm575163.htm. Accessed April 6, 2019.

6 Sharp SE CR. Cumitech 31A: Verification and Validation of Procedures in the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory. ASM Press. 2009.

7 CLSI. Verification of Commercial Microbial Identification and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Systems. 1st ed. CLSI M52. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

8 Jorgensen JH. Putting the new CLSI cephalosporin and carbapenem breakpoint changes into practice in clinical microbiology laboratories. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2012;1(2):169-170.

This article came from AST News Update, Volume . 4, Issue 2 – June 2019 which is produced by the CLSI Outreach Working Group (ORWG). The ORWG is part of the CLSI Subcommittee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST) and was established in 2015. The formation of the working group originated in a desire to efficiently convey information regarding contemporary AST practices, recommendations, and resources to the clinical microbiology community. They welcome suggestions from you about any aspect of CLSI documents, educational materials, or their Newsletters.